Behind the Skyline: Jorge Pérez on Cities and Art

December 2025, FT Chinese Columnist Fanyu Lin

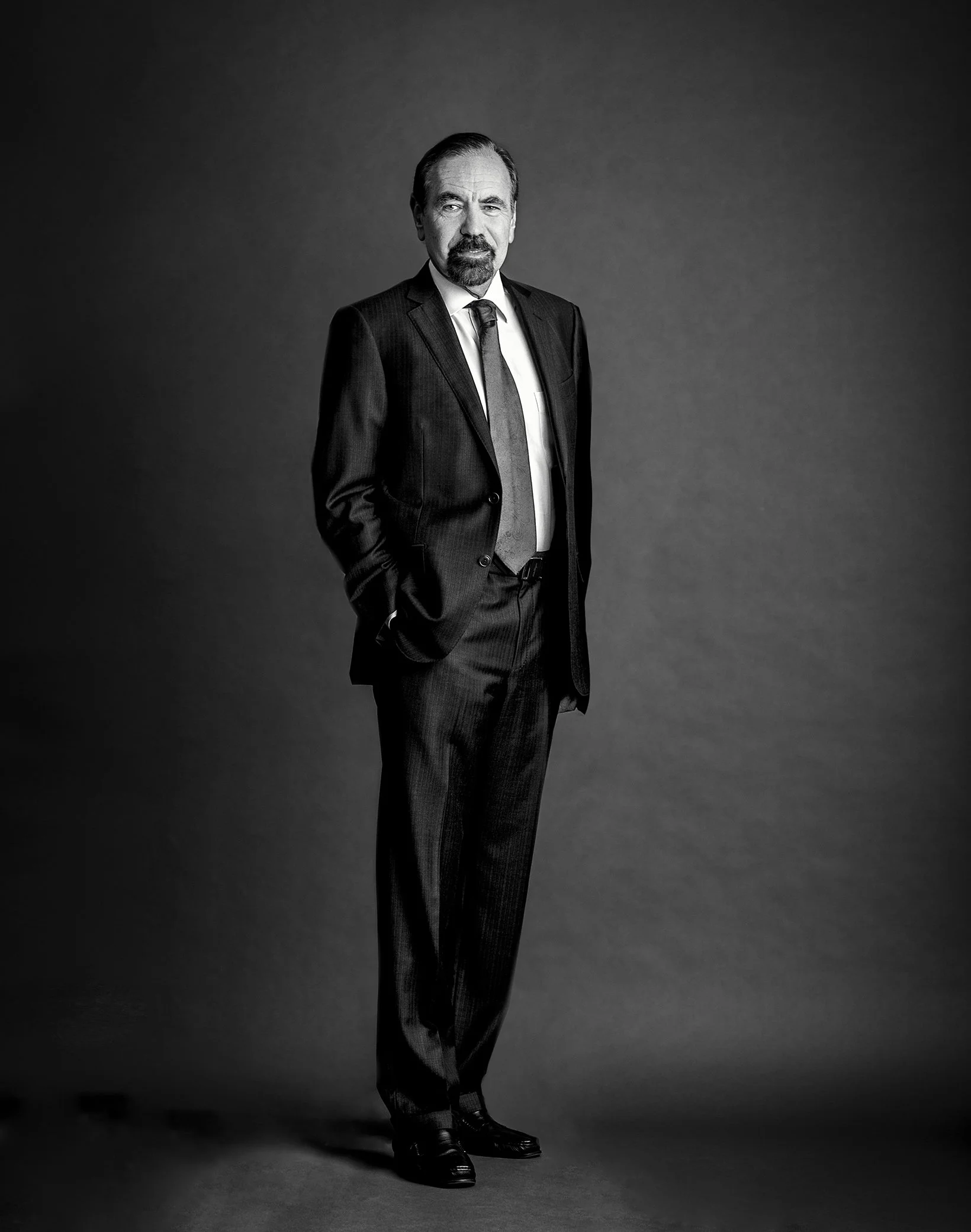

“I never thought of becoming a businessman,” Jorge M. Pérez told me when we sat down at El Espacio 23, the contemporary art space he founded, during Art Basel Miami Beach for this edition of the Global Leadership Conversation series. “I thought I was either going to be a social changer in Colombia or a professor.” He introduced himself as “HOR-hay,” lingering on the syllables with a precision that made clear how closely he holds his Latin American roots. As a major developer and one of the most visible cultural philanthropists in the United States, he speaks as someone who has built an empire yet still measures himself by where he began.

Since he founded The Related Group in 1979, the company has been instrumental in reshaping Miami’s skyline and expanding its urban core. Over the past four decades, the group has developed more than 120,000 housing units across the United States and Latin America, including one of the largest affordable housing portfolios in the country. The firm has surpassed $50 billion in real estate sales, a scale that places Pérez among the most influential figures in American real estate. His philanthropic footprint is equally extensive, with hundreds of millions of dollars donated to museums, cultural programmes, and public institutions, most notably the Pérez Art Museum Miami.

What shaped a man who became a billionaire developer without ever aspiring to be one? And how does that tension illuminate his philosophy on wealth, art, and social responsibility?

Jorge M. Pérez

Pérez Art Museum Miami, Photo by Robin Hill

The City as Destiny

Jorge’s story begins away from Miami’s skyline, in Colombia, where the daily drive up to his school on a hill took him past informal settlements with no electricity or running water. The contrast was stark, and his parents, who had fled Cuba after losing everything, impressed on him that no society could sustain such extremes. Those images stayed with him long before he had language for inequality, and long before he imagined a career in real estate.

He studied literature, philosophy, and economics as an undergraduate in New York. Later, at the University of Michigan, he pursued urban planning because he saw it as a way to confront the inequalities he had witnessed growing up. “I wanted to change the way cities work,” he recalled. European cities, dense, walkable, and intimate, offered a model of how human connection could thrive. Suburban America, defined by distance and isolation, did not.

Miami in the 1970s was a place in search of identity. It was also the ideal proving ground for a young planner driven by social purpose. Jorge worked in government, drafting housing programmes for low-income neighborhoods, advocating for mass transit, and designing policies that encouraged urban density. Government work, however, moved too slowly for his temperament. When he saw the chance to build affordable housing himself, he took it, not as a businessman, but as someone still driven by the desire to be a social changer.

The first years of his career were devoted entirely to affordable housing. The margins were thin; the motivation was social. “I didn’t care about money. I wanted to do good,” Jorge said. But he soon discovered that the private sector gave him something the public sector could not: the ability to shape the built environment with greater speed and architectural ambition. Affordable housing was tightly constrained by cost. To work with architects like Philippe Starck or Herzog & de Meuron, he needed a different financial model. The shift into market-rate development was not an abandonment of ideals, but a way to pursue design at the highest level, while continuing to build for the people who needed housing most.

Across the decades, that duality became the defining feature of his company: iconic luxury towers that command the global market paired with one of the largest affordable housing portfolios in the country. In his thinking, the two were never contradictions. They were parallel responses to the same question: what a city is for and whom it should serve. Whether that balance can ever bridge the gap between market incentives and public need is far from settled. It is a question that shadows any developer operating at his scale and one that follows him throughout his career.

Art as a Way Home

Before he ever built skyscrapers, Jorge collected lithographs. As an undergraduate in New York, “I had a full scholarship, and I made a little money playing poker,” he said. “Whenever I won, I went and bought lithographs. That was all I could afford.” His friends were puzzled. “They had posters of rock stars or baseball players. I had lithographs.” “My first three I still own,” he said. “A Man Ray, which is very conceptual; a Marino Marini, an Italian artist who is in the mix between realism and abstraction; and a Miró, which is totally surrealist and abstract.”

When he moved into urban planning, art became something deeper. He feared losing his connection to Latin America - the history, the sensibilities, the worldview he carried from home. “I felt I was going to lose my roots, lose who I am, the background that I loved so much.” he said. Collecting became his way back. Museums, artists, and collectors from the region offered him a cultural anchor. At first, he bought only Latin American art, and he attended the Latin American weeks at Christie’s and Sotheby’s each May and November. Those auctions gathered collectors from across the region. “I got not only to see the art, but to discuss politics, society, the humanities, everything with them,” he said. The rooms offered more than artworks; they offered a community and a cultural language that kept his roots alive.

Jorge’s early collection centered on what he calls “the artists of my parents’ generation”: Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera and other Latin American modernists who shaped the cultural imagination of the twentieth century. “Because that’s what I saw in the museums where my parents took me,” he recalled. When Miami’s contemporary art museum was renamed in his honour, after an initial $35 million gift, he donated that entire collection to the institution. His walls were suddenly empty. His support for the museum has continued to grow and now exceeds $100 million in art and funding. With a blank slate, his collecting life began again.

The second chapter of that life followed curiosity rather than heritage. Jorge turned toward postwar and contemporary art from Europe and the United States, and a rapidly expanding focus on artists from sub-Saharan Africa. Recent visits to Ghana and Nigeria reminded him of the social inequalities he recognised from his childhood. The contrast between immense wealth and pervasive poverty rekindled his sense of responsibility. “That gets me very sad because the world shouldn't be like that,” he said, “but it also pushes me to give back.”

Teresita Fernández, Dark Earth (Cosmos), 2019. Installation view, A World Far Away, Nearby and Invisible: Territory Narratives in the Jorge M. Pérez Collection, El Espacio 23, Miami

Chris Ofili, Blue Damascus, 2005. Installation view, A World Far Away, Nearby and Invisible: Territory Narratives in the Jorge M. Pérez Collection, El Espacio 23, Miami

Pat Steir, Autumn: The Wave After Courbet as Though Painted by Turner Influenced by the Chinese, 1986. Installation view, A World Far Away, Nearby and Invisible: Territory Narratives in the Jorge M. Pérez Collection, El Espacio 23, Miami

Violeta Maya, Mi versión del origen del mundo I-III (My Version of the Origin of the World I–III), 2024. Installation view, A World Far Away, Nearby and Invisible: Territory Narratives in the Jorge M. Pérez Collection, El Espacio 23, Miami

José Bedia, Salto transcendental de un agujero negro a una estrella (Transcendental Leap from a Black Hole to a Star), ca. 1990. Installation view, A World Far Away, Nearby and Invisible: Territory Narratives in the Jorge M. Pérez Collection, El Espacio 23, Miami

Art, for him, is not separate from civic life. It is a way of understanding others, of expanding empathy, of keeping the human dimension visible amid the metrics of development. “We have an art department that puts what I call museum-quality art in all our projects, including our affordable housing,” he said. “Art allowed me to see the world in different ways. It expanded my mind. It made me more understanding of people. That is why I say it makes you a more complete and better person, in my opinion.” He wants residents to have that same access. “We write books on the art and give them to the people in the building so they can understand the works we are putting there. It is not only going to be beautiful for the building. It is going to have that impact.”

His philanthropy reflects the same belief in art’s civic purpose. The Pérez Family Foundation, launched in 2015 by Jorge and his wife, Darlene, funds art education, supports children’s museum visits, and donates major works to museums in the United States and Europe. It is, in his phrasing, a “democratic process,” an effort to position art as a public good rather than a private luxury.

Inheritance of Purpose

Success came almost inadvertently. Jorge worked obsessively, researched relentlessly, and admits that luck played a generous role. “Fifty percent hard work, twenty-five percent luck, twenty-five percent intelligence,” he likes to say. Now his sons run much of the company’s daily operations. He has shifted into what he calls the third stage of life: giving.

Purpose, rather than accumulation, may be the inheritance he hopes to pass on. He joined the Giving Pledge and wants to give not only half of his wealth but “as much as possible while alive.” Art collections, including recent gifts to Tate Modern, the Museo Reina Sofía, and the Pérez Art Museum Miami, will ultimately go to the public. His children may keep a few pieces, but “they should build their own collections,” he said. Museums, in his view, depend on private philanthropy to survive. Without it, many American institutions would struggle to keep their doors open.

Pérez Art Museum Miami, Photo by Armando Manny

His commitment to the arts sits alongside a deeper preoccupation with the structural challenges facing the cities he helped shape. One of his most urgent concerns today is housing affordability. The problem is severe in Miami: middle- and working-class residents spend half their income on rent. Federal support for affordable housing has eroded, leaving cities dependent on patchwork funding from local and state governments. “Without public subsidies, affordable housing simply cannot be built,” he said. It is, in his view, one of the defining policy challenges of our time.

Jorge Pérez built an empire but never abandoned the mission that led him into the field. His life’s work may argue that private ambition and public responsibility need not be opposing forces, though the balance is delicate and the contradictions real. For him, cities reflect the values of those who shape them, not through policy alone but through imagination, responsibility and the decisions we make about what we build, what we share and what we leave behind.