How the Met's Embodiment of 'Universality' Made It the World's Premier Cultural Destination

July 16, 2024 Fanyu Lin for Financial Times (Chinese)

In the latest Global Leadership Conversation Series feature, I had the pleasure of speaking with Max Hollein, Director and CEO of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (the Met) in New York City. With the city's skyline as our backdrop, Max's eyes sparkled with passion as he shared, "The museum is basically the home away from home for all these different communities." This strong sense of inclusivity, he explained, has been the heartbeat of the Met since its inception, driving its mission forward into the new era.

Max Hollein. Photo by Lelanie Foster. Courtesy of The Met

As our conversation unfolded, it became clear that the Met is not just a repository of art; it is a living, breathing testament to humanity's collective journey, a place where past and present converge in a celebration of cultural unity by embracing multiple narratives of our shared story. We have to listen to each other, even when we don't agree, we have to listen to each other's narratives, with open hearts and with empathy. Although challenging, this openness can lead to profound healing, learning, and transformation.

You have artworks that can completely shake you, you have artworks that can be totally confrontational, artworks that basically put you in a level of discomfort or where you absolutely disagree. I think it's through art that you can still have a discourse, maybe with yourself first, but also a more public debate that is not immediately confrontational or binary, but more complex.

- Max Hollein, Director and CEO of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

A Humble Beginning with a Grand Vision

The origins of the Met read like the opening scenes of a historical epic. Unlike many European institutions founded on princely or courtly collections, the Met began with nothing more than a dream. “At the very beginning, this museum was just an idea very different from a lot of other, especially European institutions. This museum was founded with no collection, not a single work of art, not a building, and almost no money… But it was always meant to be a museum for the people,” Max elaborated.

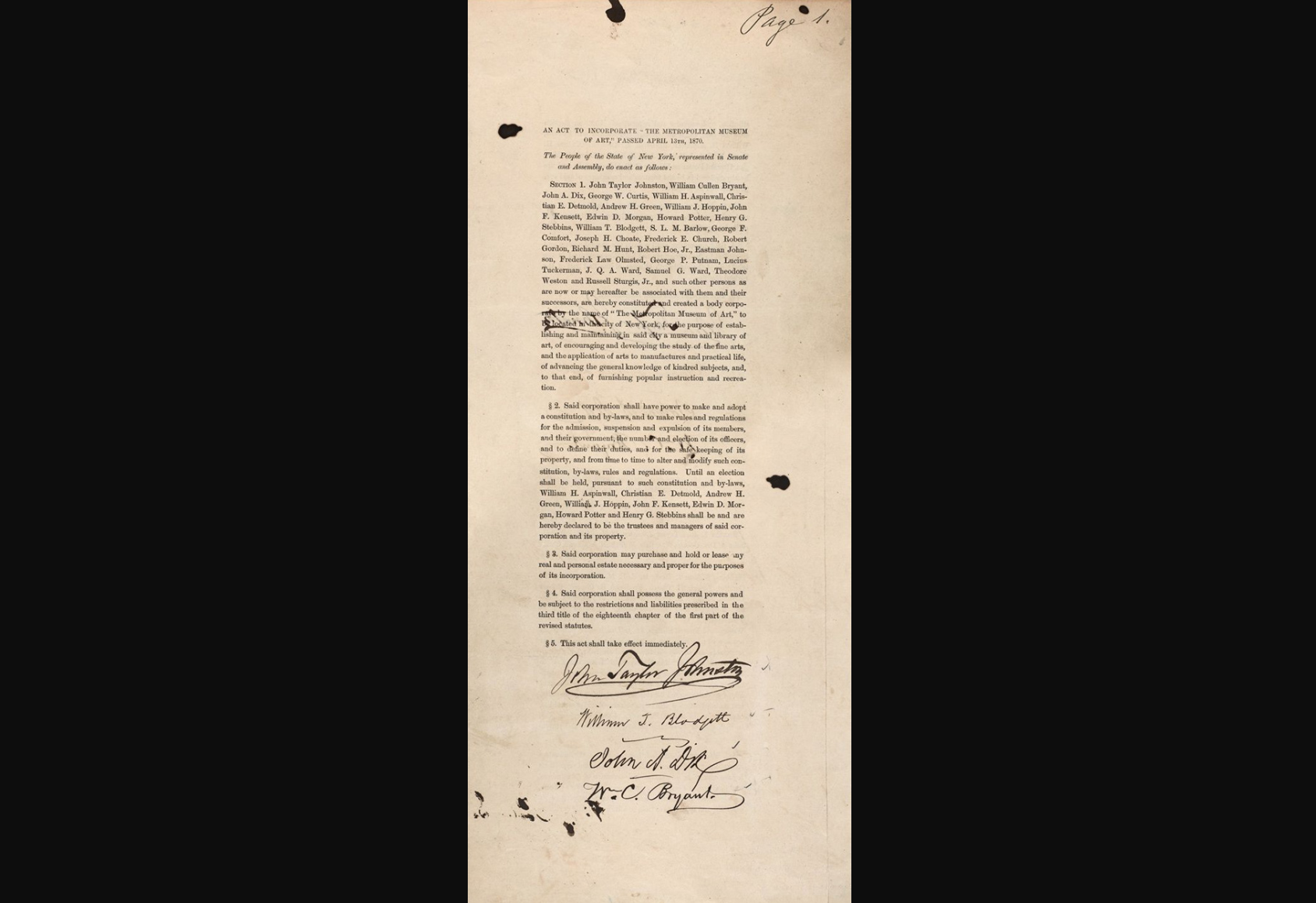

In the mid-19th century, a group of visionary New York businesspeople, inspired by their travels to Paris, envisioned a similar cultural center for their burgeoning city. Officially incorporated in 1870, the Met began with modest means but a grand vision: to serve as a museum for the citizens and the people, with a strong educational mission at its core.

Met Museum Charter. Courtesy of The Met

This openness nurtured the early development of the museum. Driven by this vision, the Board of Trustees successfully raised operating funds, amassed a foundational collection, and hosted exhibitions in rented spaces. In 1880, the Met found its first permanent home at 1000 Fifth Avenue. By the turn of the century, it stood proudly among the world's premier art institutions. Today, the Met houses an incredibly diverse collection that spans various cultures and eras, continually refining and reorganizing its galleries to foster cultural understanding and dialogue.

The Met Fifth Avenue. Courtesy of The Met

Shaping Cultural Narratives

As the Director and CEO, Max finds fulfillment in guiding an institution that not only generates excitement but also actively participates in shaping cultural discussions. "It's an enormous privilege and joy to work in a place that shapes and transforms our understanding of culture and living together," he reflects.

Max consistently champions the museum's commitment to inclusivity and challenging traditional narratives. Art, historically commissioned for various social, political, and propaganda purposes, often surprises people with its complexities and multifaceted roles. Max explains that unveiling the true purpose of a 15th or 16th-century artwork can be both shocking and enlightening. At the Met, the goal is to present and contextualize these masterpieces within their complex historical settings.

The Met has undergone a significant transformation over the past two decades. Once a museum that merely informed visitors about art, it has evolved into a platform that convenes diverse voices. Max emphasizes the importance of allowing visitors to experience their own journeys through art, fostering a dynamic cultural discourse. "We bring you together with many different voices, inviting you to look at art and each other in multiple ways," he explains. This approach moves beyond a Eurocentric narrative, embracing multiple vantage points, much like Akira Kurosawa's influential film Rashomon, where various characters offer subjective, alternative, and contradictory versions of the same event. This transformation positions the Met not just as an opinion leader but as a place where diverse perspectives converge.

Through openness, the museum is reconstructing historical narratives and shaping contemporary ones. To reflect the fluid and multifaceted nature of today's world, Max emphasizes, “It’s more important for us, in regard to the art of the current time, to have a very diverse collection or a very diverse presentation of artworks and artists in order to create a similarly complex understanding of today, as we are reinterpreting our collection in regard to the past.”

He believes that art should challenge and provoke, not just offer comfort and beauty. Great art can be confrontational, pushing viewers into discomfort and disagreement. This very discomfort can spark deep personal reflection and public debate, which are essential for a nuanced understanding of complex issues. The Met actively invites artists whose works challenge us in this way. In Max’s words, “I'm also looking for some of these artworks and artists to expand our horizons or even just confront us with other truths and other complexities.”

One such artist is Kent Monkman, the renowned Cree artist from Canada. Commissioned to create two monumental paintings for the Met's Great Hall, Monkman is celebrated for his bold and provocative reinterpretations of Western European and American art history. A haunting aspect of Monkman's work is his gender-fluid alter ego, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, a time-traveling, shape-shifting, supernatural being that often takes center stage in his pieces. By turning the colonial gaze on its head, Monkman challenges conventional narratives of history and Indigenous peoples, inviting viewers to question and rethink the stories we've been told. His work is a compelling call to engage with the deeper truths of our shared past and present.

Installation view of The Great Hall Commission Kent Monkman, mistikôsiwak (Wooden Boat People), 2019. Courtesy of The Met. Photo by Anna-Marie Kellen

The museum’s rooftop is another stage for powerful narratives. “In a much more poetic way, if you would go to the roof right now, Petrit Halilaj's installation tells you the story of himself as a refugee kid from Kosovo during the war. He basically, through these works, tells the story of children, how their lives have been uprooted, and what their aspirations are,” Max describes. Halilaj’s works, depicting the dreams of school and the sense of home and belonging, resonate deeply in today's world. It reminds us of the transformative power of childhood imagination in recounting historical events, drawing from his personal experiences in his homeland while reflecting a universal longing. Halilaj dedicated this work to children around the world whose lives have been disrupted and scarred by war, hoping that "their dreams will fly us to a better future.”

The Roof Garden Commission Petrit Hallilaj, Abetare. Petrit Halilaj, 2024. Courtesy of The Met. Photo by Eileen Travell

A Universal Museum with Contemporary Relevance

Max envisions the Met as a contemporary institution, not confined to contemporary art but engaging with art across cultures and eras through a modern lens. "Our goal is not completeness but universal relevance," he asserts. “I want to make sure that we, as an institution and with all the art that we have and how we show it, have a universal relevance across the globe, not only by being important or prominent, but really by being able to engage with very different communities about the appreciation of art, discourse about life, their culture, and all these different aspects that make us human beings. That fosters also a deeper cultural understanding of each other.”

This vision extends far beyond preserving and showcasing art. It encompasses an ambitious investment in updating not only its infrastructure but also the intangible assets of curatorial and academic understanding, the nuanced presentation of exhibitions, and the thoughtful design of collections—all of which are encapsulated within the museum's architectural framework. This includes a monumental $2 billion investment to transform a quarter of the museum's gallery space.

The Met Fifth Avenue, Nighttime View. Courtesy of The Met

Max speaks passionately about the Met's role as the custodian of its vast collections: "We have great collections, and it shouldn't be as if we just have this as a gold medal. It's a responsibility.” The museum's ongoing transformation includes significant architectural projects involving cutting-edge architects from around the world. These projects not only reflect the Met's commitment to showcasing its collections in the most up-to-date and engaging ways but also ensure that the institution remains at the forefront of cultural presentation, continually driving profound healing, learning, and transformation through openness.

The Met operates under a complex, multi-layered structure, and a multinational board of over 100 members and staff of almost 2,000 from all over the world. These individuals come from diverse backgrounds, representing not only New York but various regions around the world. This diversity further allows the Met to approach its mission from a global perspective, ensuring that its priorities and initiatives reflect a broad range of cultural insights.

One of the most significant projects under Max's leadership is the plan for the new Oscar L. Tang and H.M. Agnes Hsu-Tang Wing for Modern and Contemporary Art, which will replace the Museum’s current galleries for contemporary art. This wing will be a major showcase of the museum’s renowned holdings of 20th- and 21st-century art, offering a globalized view of the period's artistic achievements. The Met's inclusive and wide-ranging collection philosophy recognized musical instruments, arms and armor, costumes, and textiles as art forms. This broad understanding of art will be reflected in the new wing, which will invite visitors to make connections between works from the 20th century with those from across the collection, highlighting the continuity and evolution of artistic principles across time and cultures.

The modernist appreciation for imperfection, often seen as a groundbreaking achievement of Western modernism, can also be found in 17th-century East Asian lacquer art. By presenting such cross-chronological comparisons, the Met aims to expand the public's understanding of modern art, demonstrating its deep roots in diverse cultural traditions.

The financial commitment to this vision is substantial. The Oscar L. Tang and H.M. Agnes Hsu-Tang Wing for Modern and Contemporary Art, named after the couple's historic lead gift of $125 million, exemplifies this commitment. The museum has recently raised $550 million in private donations for this new wing, which is being designed by Frida Escobedo, the first woman to design a wing in the museum’s 154-year history. It will feature accessible galleries that highlight diverse artists and narratives, ensuring that visitors from all walks of life feel at home. The project has garnered support from local, national, and international levels, creating thousands of jobs and furthering the Met's impact on the creative economy.

Met Museum Plaza. Courtesy of The Met

The Met's ambitious transformation under Max Hollein's visionary leadership isn't just about change; it's about revolutionizing the way we engage with the world. By fostering deeper cultural understanding and presenting art in ways that resonate with contemporary audiences, the museum marries the needs of today with the richness of its history as a dynamic, living institution. In the ever-evolving narrative of human creativity, the Met stands as a timeless chapter, a testament to the enduring power of art to bridge divides and inspire future generations.